Introduction

When your hear "magical girl," what kind of character do you imagine? Maybe some people imagine female warriors in flashy costumes. However, magical girl fictions were not always like that. Sally the Witch is one of the genre originators, but she does not usually fight. When and how did they start fighting? Why are they called magical girls today? People give various explanations, but they do not necessarily give answers to my question. I wanted to know more information. That is the starting point of my interest.

In the previsous post, I analyzed how the term "maho shojo"/ magical girl was developed. My conclusion was that it became common from the middle '80s to early '90s. However, I did not describe how the magical girl concept led to the current fighting magical heroines. I would like to solve that problem this time.

To analyze the process, I would like to check the whole history of magical girl genre. The topics cover magical girls and fighting heroines with costumes/ transformation ability. I skip other similar genres such as sword-and-sorcery fantasy, RPGs, and wizard school fictions. I do not cover foreign wizard fictions either. I would like to concentrate on Japanese magical girl fictions and some similar fictions.

However, I do not take an essentialist attitude toward the genre definition. Maybe I could argue something like, "This is the definition of the magical girl" or "That piece of fiction is NOT magical girl," but I would like to avoid it as much as possible. I still skip some fictions, but that is just because I do not want to make the discussion too broad.

Timetable

Here is a chronological table of magical girl fictions and fighting heroines. Please click and scale the image. This part only covers fictions from the '60s to '70s. It is not a wholesome list, but it includes important fictions from each era. I divided those items into three categories:

A. Supernatural heroines

B. Henshin warriors

C. Fighting magical girls

Category A includes heroines who have supernatural power without fighting.

Category B includes fighting heroines in costumes or fighting heroines with henshin/ transformation ability. I exclude some costume characters such as modern military soldiers.

Category C is more specific than other categories. It includes costume warriors who have "maho shojo" in their titles or names. Other category names such as Sailor Guardians or PreCure are not included. That category is linked to the main topic: When and how warriors became "maho shojo."

The purpose of this series is to analyze the development of Category C: Fighting magical girls. It is just a categorization for the theme. It does not mean that there are definitive differences between those three types.

I also divided the media into three types:

Publishing

TV + homevideos

Videogames

Those three types of media have unique history and tendency. It is also important to analyze how those media have influenced each other.

1. Prehistory: Before 1962, Shojo Manga and Faust

We need to start with shojo manga/ manga for girls. Shojo manga had fighting heroines way before the emergence of magical girls. For example, Katsudi Matsumoto made Nazo no Clover, a masked heroine shojo manga, in 1934. *1 It is even before WW2.

Kyuta Ishikawa made Super Rose, a superheroine shojo manga, in 1959. *2

They were not necessarily the mainstream of shojo manga. Many other manga in shojo magazines kept pre-existing tropes from older manga and literature. It is said that they had big three categories in those days: *3

1. Fun manga: Girls' slice-of-life and comedy. Or tomboy princesses' stories. It is a very old and common type of manga. Such manga can be seen even in pre-WW2 newspaper cartoon.

2. Sad manga: Girls' melodrama, typically about separations of mothers and daugters. Such stories can be seen in other media for kids, such as literature, kamishibai, and emonogatari, too.

3. Scary manga: Stories of girls getting involved in mysterious cases. Or detective girls' adventures/ thrillers. In the '60s, horror became a popular genre too.

They were not necessarily regarded as "genres," but some magazines categorized shojo manga in that way. Shonen magazines include manga like category 1 and category 3, so maybe I should call them sub-genres of kids mang in general. Back then, the boundary between shojo media and shonen media were more vague. *4

Here are examples of those three categories:

1. Fun manga: Yoko Imamura's Chako-chan no Nikki (1959) was serialized in various magazines. It depicts an energetic girl's happy but troublesome life with her family and friends.

2. Sad manga: In Yuyake no Kyoku (1958,) Mitsuo Higashiura depicted a girl confronting a lot of tragedy such as construction troubles, injure, bullies, bankruptcy, etc.

3. Scary manga: In Momoko Tanteicho (1957,) Mitsuaki Suzuki depicted a detective girl's adventure. She solves various mysterious cases with her friends.

We should also remember that adaptations of classic folk tales and literasure were still common around the '50s. *5 When we consider magical girls' history, we cannot ignore Cinderella's influences.

There were also a rise of TV shows and a fad of child actors. Child actors such as Tomoko Matsushima appeared in covers, articles, and manga. Girls admired those little actors just like they admired ballerina and princesses.

That was the situation of shojo manga. Humorous slice-of-life, mother-daughter tragedy, detective thrillers, folk tales, literature, and celebrities. Romance was not a thing yet. Osamu Tezuka depicted some romance in shojo manga, but it was not a main theme in monthly shojo magazines. Plus, many stories were set in real, poor Japan. Shojo manga maintained some vernacularity.

Osamu Tezuka was a pretty unique creator in the post-WW2 shonen and shojo manga. He inherited science fiction + fantasy from older manga generations and often adopted such progressive themes. He was a leading manga creator and a time capsule of old manga at the same time.

In 1948, Tezuka made Magic House. It is a story of a conflict between science and magic. A female magical supervillain Hydra appears in the manga. Hydra betrays the magical world and sides with science. Maybe we can call her the first magical girl even though she is not the protagonist. The design is obviously under the influence of American superhero comics.

In 1950, he adapted Goethe's Faust into a manga. In that manga, God sends Mephistopheles to the earth to test his ability. Marguerite is supposed to be an earthly form of an angel. The angel Marguerite saves Faust at the end of the story. From the current viewpoint, it looks pretty similar to the magical girl trope.

In Princess Knight (1953,) he depicted Heckett, a daughter of Mephistopheles. She uses various magic such as fire, telekinesis, and transformation. Some parts of the manga suggest that Tezuka reused some ideas from Magic House in the series.

Plus, the series depicts an angel sent to the earth for a mission. That is probably a variation of the Faust. As I mentioned above, Tezuka had already adapted Faust into a manga. Faust's plot is linked to the origin of the magical girl genre.

Tezuka also depicted a heroine with a secret identity and metamorphosis magic in Princess Knight. Especially metamorphosis is a common theme of his manga.

We cannot confidently say Tezuka is the originator of the magical girl genre. Princess Knight and the other manga did not have common tropes of the genre. However, we should not ignore Tezuka's influences on post-WW2 manga in general. His importance becomes clear in the analysis of Sally the Witch.

2. Himitsu no Akko-chan: The Originator (1962)

2-1. Akko-chan's Story

In Ribon magazine 1962 May issue, Fujio Akatsuka started Himitsu no Akko-chan. It is arguably the first magical girl manga. How does the story begin?

Akko is an ordinary girl. She admires Cinderella and movie stars. She wishes she could be like those heroines. She sometimes sees an imaginary version of herself in her precious mirror.

One day the mirror is accidentally broken. When she is feeling sad about that, a strange man with sunglasses appears. That man says he came from a mirror world. Since Akko took care of the mirror for a long time, he gives her another mirror. People in the mirror world can read other people's minds. The man says the new mirror can grant Akko's desire.

Akko says her aspirational self image backwards in front of the mirror, like "sserd ycnaf ni lrig etuc" (cute girl in fancy dress.) Then, she transforms into a pretty girl. She decides to keep it a secret for herself. That is why the title includes himitsu/ secret.

Akko transforms into various forms to help other people or to play pranks. She sometimes faces troubles such as kidnapping or quarrels with her best friend. That is the premise of Himitsu no Akko-chan.

2-2. How Akko-chan Was Made

The basic style of the manga is humorous slice-of-life. It was pretty common in shojo manga. Akatsuka started to make shojo manga in the '50s, but he used to make sad manga and scary manga in the early phase. In the late '50s, his style shifted to slice-of-life. For example, he made Ohana-chan in 1960. It is a slice-of-life manga about an energetic girl.

Akko-chan inherited such a basic, humorous style of manga.

Interestingly enough, Akatsuka's assistant/ wife Tomoko Inao deeply got involved in the development of Akko-chan. Akatsuka consulted with Tomoko during the production, and she even made draft of the protagonist's design. *8

Partners' involvement can be seen in many manga artists. Tomoko helped some popular projects in Akatsuka's early career. She is a very important person for both Akatsuka and the beginning of the magical girl genre.

2-3. The Inspiration Source for the Magical Story

How did Akatsuka come up with the magical story?

In a middle '70s interview, Akatsuka himself talked about the inspiration source *9:

Akatsuka:

I explained the idea to the vice chief editor of Ribon. I said a girl transforms with a mirror, but he didn't take it seriously. He was like, "Magic? That's so ridiculous and outdated." I insisted because nobody was making a magical manga at that time. Akko-chan became unexpectedly popular, so I made many chapters. And, just coincidentally, Bewitched started.

Wada:

Did Bewitched start later?

Akatsuka:

Yes, I was like, "Lucky me!" To tell the truth, Eiga no Tomo magazine is the inspiration source for Himitsu no Akko-chan. I subscribed to that magazine. It had journals about foreign movies, right? One day I checked some old issues and found "I Married a Witch" in the journal. That title was so impressive.

Wada:

That is René Clair's film. I Married a Witch and Bewitched were released under the same Japanese title. Bewitched is actually a TV version of I Married a Witch.

Akatsuka:

The phrase "I Married a Witch" felt so fresh.

In other words, "I Married a Witch" was just a trigger. Akatsuka was inspired by the phrase without watching the movie. *10 The other elements of Akko-chan are faithful to the '50-'60s shoujo magazines's style. He brought magic into that pre-existing formula.

We should also remember that Akko mentions Cinderella in the first chapter. It seems like Akatsuka's magical images were inspired by children's literature, not by witchcraft. The mirror and the reversed words remind us of Through the Looking-Glass. The magic in Akko-chan was probably associated with popular literature.

2-4: Who Is the Guy From the Mirror World?

The most mysterious part of the original manga is the guy with sunglasses. He is not a malicious character, but he has suspicious atmosphere. Where did that idea come from? He reminds us that old shojo manga had many detective mystery and thrillers. Gangs with sunglasses often appeared in shojo manga. Those mysterious men sometimes turned out to be main girls' family. For example, in Tetsuya Chiba's Yuka wo Yobu Umi, a mysterious guy with a dark shirt is the protagonist's father. Supporting daddies with secret identity were so common in shojo manga. I guess it was a under the influence of litrature such as Daddy-Long-Legs.

The beginning of Akko-chan can be summarized as follows:

Under the influence of "I Married a Witch," Akatasuka brought the transformation magic like classic literature into Akko-chan. He mixed it with common shojo manga materials. Akko-chan was just an ordinary slice-of-life manga except the magical part. In other words, Akatsuka conveyed the new magical story in the very familiar style.

3. Sally the Witch: The Popularizer (1966)

3-1. It's a Wonderful Life and Chibikko Tenshi

In Ribon 1966 July issue, Mitsuteru Yokoyama started Sally the Witch. However, we need to take some detours before analyzing that series.

In 1946, Frank Capra made It's a Wonderful Life, one of the most iconic American Christmas films. It is a story of a loan company manager called George Bailey. When George is about to commit suicide in despair, Clarence, a guardian angel second class, appears. Clarence shows an alternate reality where George never existed. George stops suicide and comes back to the reality. He celebrates the town and his own life.

Japanese premiere of the film was in 1954. Many manga creators have been inspired by (,or they mimicked) American films and fictions. It's a Wonderful Life is one of them. The most famous example is Shotaro Ishimori's debut manga Nikyu Tenshi (1955.)

Nikyu Tenshi is a story of a second-class angel Pint. Pint does not have his wings yet. To get wings and become the first-class angel, he has to achieve ten good things in the human world.

Mitsuteru Yokoyama utilized a similar idea in his shojo manga series Chibikko Tenshi (1963.) Maybe he was inspired by Ishinomori's Nikyu Tenshi or It's a Wonderful Life. There is no information about it.

Chibikko Tenshi is a story of two angels called Tylulu and Malulu. I suppose their names stem from The Blue Bird. Those two angels do not have their wings yet because they do not know good and evil. Lord Above tells them to go to the human world and learn from human beings.

Tylulu and Malulu transform into human. They help people with their supernatural power, but they make mistakes due to the lack of knowledge about human beings. They sometimes face despair caused by a devil or social problems such as alcoholic. At the end of the series, they go to another town.

That is the story of Chibikko Tenshi. As you can see, it is under the influence of It's a Wonderful Life or Nikyu Tenshi. Such a story was not anything new to Yokoyama. In 1955, eight years before Chibikko Tenshi, he already made a manga adaptation of Dickens' Christmas Carol.

The important thing is that Chibikko Tenshi became a beta version of Sally the Witch. Hiromi Seki from Toei Animation wrote about that *11:

When I entered Toei Animation, I met older producers. They remembered the production of Sally the Witch. I was surprised to learn that Sally has another origin made by Yokoyama-sensei. They told me the title "Something Tenshi," but I forgot the first half.

It's a Wonderful Life, especially the idea of "angels with missions on the earth" became a very important origin of the magical girl genre through Chibikko Tenshi.

To fully analyze Sally, we should also check some other inspiration sources.

3-2. Other Inspiration Sources

3-2-1. Fantasia

In 1940, Disnesy released Fantasia. The Japanese premiere was in 1955.

Fantasia had big impact on Japanese pop culture. Even in the WW2 era, Mitsuyo Seo watched and got inspired by it. Later, Osamu Tezuka was inspired by Seo's anime. Tezuka was indirectly inspired by Disney even before the end of WW2. That is one of famous origins of Tezuka's creativity.

Needless to say, The Sorcerer's Apprentice has some influences on the magical girl genre. Mickey shows some images of magic, such as hand gestures and particle effects.

Night on Bald Mountain is important too. That sequence is filled with ghosts and monsters. There is a gigantic demon with horns on the top of the mountain. I suppose such an image of dark world had some influences on magical girl fictions, especially on Sally. *12

3-2-2. Gothic Horror and Haunted House

The history of gothic horror films dates back to the pre-WW2 era. Many horror films were made by Universal. In the '50s, Hammer Film Productions made gothic horrors films and monster films. Horror became a pretty popular genre in Japan too.

In 1957, Mitsuteru Yokoyama made Hakaba kara Nozoku Me, his first manga about vampire. In 1958, he depicted a vampire again in Beni Koumori. *13 He often utilized horror elements in his manga.

Yokoyama knew the haunted house fictions too. In 1956 and 1966, he adapted Edgar Allan Poe's The Fall of the House of Usher into manga twice.

3-2-3. John Buchan's The Magic Walking Stick

In an interview, Mitsuteru Yokoyama cited John Buchan's The Magic Walking Stick as a main inspiration source for Sally. *14

The Magic Walking Stick is a story of a teenage boy Bill. One day Bill gets a magical stick from a mysterious old man. That stick allows him to visit any place he wants. With the stick's magical power, Bill rescues a foreign prince from a coup.

It seems that The Magic Walking Stick was a very popular juvenile in the old days. Fujio, Fujiko F. cited it as an inspiration source for Doraemon. I suppose it was an archetype of light-hearted magical stories to some generations.

3-2-4. Bewitched and Rom-Sit-Com

In 1966 February, Bewitched started airing in Japan. Mitsuteru Yokoyama watched it and immediately made a concept of "cute witch" manga. The title was Sanny the Witch.

Before the Japanese broadcast, Yoshinori Watanabe from Toei knew the American witch sit-com and was thinking of making a Japanese version. In 1966 May, Watanabe saw a teaser for Sanny the Witch in Ribon magazine. He immediately called Yokoyama and got the rights for TV adaptation. Due to a trademark conflict, the title was changed to Sally the Witch during the production. In the same year, I Dream of Jeannie started airing. People noticed that witch became a trend.

3-2-5: Osamu Tezuka and Princess Knight

It seems like some elements of Sally were inspired by Osamu Tezuka's manga. Chibikko Tenshi's angels are depicted similarly to the angels from Princess Knight. Plus, Sally's dad looks pretty similar to Saturn. Saturn appears in many Tezuka manga, such as Magic House, Astro Boy, Princess Knight, etc.

3-3. The Story of Sally the Witch

Sally (Sanny) begins as follows:

At a starry night, one starlight gets big and comes down to the earth. That light gradually changes into a Western styled mansion.

Next morning, people in the neighborhood notice the mansion and wonder why it suddenly appeared. A thief thinks it must be a rich man's house. That night, the thief sneaks in the mansion. However, he notices that the interior is old as if it were abandoned long ago. When he enters a room, he finds out that it is linked to "devils' world."

Then, a cute girl Sanny appears and saves the thief. She erases his memory and sets him free. Devils and Sanny's mom complain about her decision, but she does not change her mind. She tells the reason why she came to the earth. She is intrested in human beings and wants to become friends with them. Sanny's mom accepts her decision. Next morning, Sanny meets other school girls and goes to school.

In other chapters, she solves problems around her with magical power.

In chapter 2 and 3, Sally's dad/ the devil king comes back from a long journey. He gets angry at Sally's behaviors. He comes to the human world and tries to bring her back. Thanks to the mom's help, Sally convinces him to let her stay in the human world.

As you can see, Yokoyama perfectly utilized all the elements I mentioned above: Fallen angel (devil,) Fantasia, the dark world, monsters, haunted house, cute witch concept, etc.

Sally the Witch did not inherit the romantic element from the predecessors such as Bewitched or I Dream of Jeannie. Kids watched those TV shows, but neither Bewitched nor Jeannie was supposed to be a kids show. On the other hand, Sally was kids manga/ show from the beginning. It has a little romance of side characters, but that was not fully pursued. As I mentioned earlier, monthly shojo magazines avoided romance back then. However, a big change was coming to the media.

4. Who Inherited Romantic Comedy

Shojo magazines did not have much romance in the monthly magazine era. However, as some weekly shojo manga magazines appeared in the early '60s, shojo manga's styles started to change. *15

In 1963, Hideko Mizuno adapted Roman Holiday into manga and also started serializing Suteki na Cola, a romantic Comedy based on Billy Wilder's Sabrina. For a short period, Mizuno released some Hollywood-like romantic comedy manga in shojo magazines. Mizuno herself was dissatisfied with that style and moved on to more complicated themes, but other creators from rental manga or newbie awards kept making romantic comedy in their own way. Since many shojo magazines were launched in that era, there were new posts for those creators.

In 1967, Masako Watanabe adapted Bewitched into manga in Weekly Margaret. It shows what kind of story was popular in the weekly magazines. *16

Miyoko Motomura's Okusama wa 18-sai (1969) is the most typical example of the trend. It is a story of young married couple. The wife is an 18 y/o girl, and her husband is a professor working in a college. One day she realizes that her husband is so popular with female students, so she enters the college to watch him. Since they do not reveal their relationship in the college, they often cause troubles.

That manga became so popular that it was adapted into a TV series in 1970. It is obviously under the influence of Bewitched. The title is loosely based on Okusama wa Majo, the Japanese title of Bewitched.

I think some parts of Bewitched and Jeannie were inherited by the rom-com shojo manga. On the other hand, the earliest magical girl fictions rooted in the old style of the monthly magazine era. The authors of those older manga tended to be male while the authors of rom-com manga were young female creators. There was a gap between those two types of shojo manga. The elements of Bewitched and Jeannie were separated into two different types of shojo manga.

5. Early Map of Magical Girls and Others

The history of early magical girl manga and inspiration sources can be summarized as the image below:

The map roughly shows the early magical girls and their predecessors.

Himitsu no Akko-chan and Sally the Witch made the core image of magical girls. Or I should say Toei Animation's anime series retroactively turned them into the archetype of the genre. Akko-chan is an ordinary girl who happened to get magical power. Sally is a witch from another world. The two originators set the standard of the genre.

From the next chapter, I describe how Toei Animation developed it.

6. How Sally Was Adapted into Anime (1966)

Since the anime project of Sally started in the very early phase of serialization, there were only a few epsiode of the manga. Plus, Yokoyama did not continue the manga for a long time because he was busy with other projects. Toei Animation themselves had to prepare materials for the show.

First, Sally's iconic spell "Mahariku Maharita" is anime-original. It does not appear in the manga. The lyricist Asei Kobayashi made the spell for the OP lyrics. Later, it was used in some anime episodes. *17 Mahariku Maharita is one of the most iconic magical girl spells, but Sally did not often use it. I think the idea of the magical girls' spell was completed in Akko-chan.

Second, Toei Animation added side characters. The characters, such as Cub, Hanamura Triples, and Poron, are anime-original. Yoshiyuki Hane made those characters. Plus, the character design for Sally's friends was changed. Some of those elements were brought into the original manga.

They also changed the "devils' world" into "magical world." Maybe they avoided the religious tone, but I'm not sure about that. The devilish, gothic horror element was watered down.

They borrowed some elements from Bewitched and Jeannie. Sally sometimes uses magic by wink. It cannot be seen in the early chapters of the manga. In the manga, Sally uses magic with hand gestures just like Micky from The Sorcerer's Apprentice. I guess the wink was inspired by blink from Jeannie. Later it was used in the manga as well.

The anime staff needed to prepare a lot of ideas for the episodes. Young writers such as Shunichi Yukimuro joined the team, and many directors wrote the script under alias. *18 For example, Minoru Hamada is an alias of Yugo Serikawa.

They brought popular materials from shojo fictions:

Episode 17 is a story of identity switch with a princess.

Episode 28 is a ballet story. Ballet was a very popular element in shojo manga. The episode includes various sad shojo manga cliche such as bully girl or sudden accidents.

They were also inspired by the '60s hot topics:

Episode 40 depicts a latchkey kid's sadness. Latchkey kid was a new phenomenon in the '60s.

In episode 73, they explain red tide/ algal bloom. Red tide caused by economic growth became a social problem in the '60s.

Such a journalistic/ educational style was inherited by some of Toei Animation's magical girl anime.

They also developed the world of Sally:

Episode 35 depicts Yama and East Asian image of hell/ Diyu.

In episode 48, "God" appears, and it is revealed that Sally's dad/ the king of the magical world is under the control of the god.

Interestingly enough, Sally also has a battle against an evil magical girl:

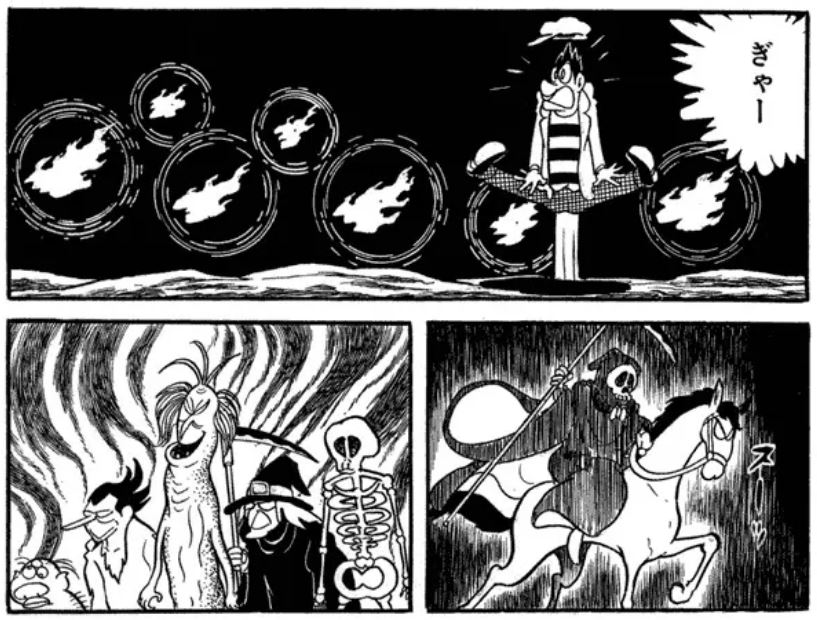

In episode 31, a witch Barbara appears and attacks Sally. Barbara uses lightning, and Sally reflects it with a round barrier. It is an interesting attempt to bring battles into magical girl.

The writers were allowed to write anything as they wanted thanks to Producer Takashi Iijima. He did not even request any theme in briefings. Shunichi Yukimuro wrote, "It was the most enjoyable job." *19

Both Sally the Witch original manga and anime version prepared many basic elements of the genre and various options for the future projects. I think it's safe to say all the magical girls are daughters of Sally.

7. How Akko-chan Was Adapted into Anime (1969)

7-1. Changes in the Anime

Since Toei Animation was confident in the success of TV shows for girls, they already started developing the next project in 1966. There were some other options such as a school comedy, but they chose Akko-chan because of the similarity to Sally. *20

Some drastic changes were added to Akko-chan.

Akko did not have a particular transformation spell in the manga. She said targets of transformation backwards. Since Sally's Mahariku Maharita was pretty catchy, Toei Animation wanted to make a spell for Akko-chan too. That is why "Tekumakumayakon" was made. It is Shunichi Yukimuro's idea. *21 Yukimuro said, "When I was murmuring something like 'techniques, mirror... techniquesmirror...' I came up with Tekumakumayakon."

Unlike Sally, Akko always uses the spell when she transforms. Many magical girls have their symbolic spells for transformation today. That idea was originally developed by Toei Animation and Yukimuro.

They changed the man from the mirror world to a female fairy. Maybe they thought the man with sunglasses and a dark suit was too suspicious. They also gave regular roles to guest characters. The original manga had only a few regular characters. The stories were basically driven by those side characters.

They also added animal characters such as Shippona and Dora. Shippona is a cat owned by Akko's family. She does not have special ability, but she plays various roles in some episodes. It is said that Shippona is the pioneer of magical girls' mascot trope.

Since Sally was a pretty experimental project in a transitional period of technology, its quality and style were sometimes unstable. On the other hand, Akko-chan's visual quality and the style got more consistent. Plus, since it is a story of an ordinary girl living in an ordinary town, it gained more grounded reality than Sally.

7-2. The Rise of Merchandise and Magical Items

In the original manga, Akko used a pretty big mirror. Toei Animation changed it into a compact because they thought the carryability of the mirror was important for the story. It gave freedom to the story as the staff expected, and it also had an unexpected influence:

As the anime started, Nakajima Seisakusho, a sponsor of the series, released a toy called Himitsu no Kagami, Tekumaku Mayakon. It is an imitation of Akko's compact. It is probably the first character accessary/ role-play merch in Japanese history. Kamen Rider did not exist in 1969. There was already Ultraman, but toy makers did not make a Beta Capsule toys until the '80s. Akko-chan became a pioneer of the role-play toy. The compact made an unexpectedly big hit. It was sold out in many areas. Many girls could not buy it. The compact fad became so big that mothers all over Japan even made complaints to the TV nework and newspapers. *22

It also gave an important element to the genre. That is the magical item. Akko-chan prepared the connections between magical girls and magical devices. It became one of the most basic magical girl components.

8. Comet-san: Another Origin of Magical Girls (1967)

There is another magical girl released in the '60s. That is Comet-san. It is a live-action sit-com with some musical.

Comet-san is a story of a young girl called Comet. She is a witch from Planet Beta. Since she gets into too much mischief, a school principal banishes her to the earth and forbids her to use magic. On the earth, she meets elementary school brothers. While other people do not believe that Comet is an alien, only those brothers accept the fact. She decides to work as their family's maid. While working as a maid, she gets into a lot of mischief with kids.

8-1. How Comet-san Was Made

Unlike other magical girl shows from the '60s-'70s, Comet-san is not Toei's project. It was developed by a TV network TBS and Kokusai Hoei. TBS intended to team up with main Toei at first, but it was entrusted to Kokusai Hoei for some schedule issues. The title was Comet Mako-chan at that time. *23

The TBS producer Yoji Hashimoto gathered skilled members such as Director Eizo Yamagiwa and Writer Mamoru Sasaki. *24 Their initial concept was under the influence of Bewitched, but it turned into a Japanese version of Mary Poppins through the preproduction process. The series gained musical parts because of that. Since Japan does not have the nanny culture, the protagonist was supposed to be a maid (otetsudai-san.) And thus, they made the basic concept of "a Mary Poppins-like maid from outer space." The idea of maid superheroine was inherited by some fictions later.

8-2. Modern Kids: The Theme of Comet-san

The creators of Comet-san intended to depict "modern kids." *25 Back in the early '60s, some teachers and authors discussed the mentality of modern kids and criticized the current school education. They analyzed how modern kids develop their mindset through the massmedia experience outside schools. The entertainment industry quickly reacted to the trend. Some manga magazines labeled their manga as "modern kids' manga." Yoko Imamura's Chako-chan is a typical example. Comet-san was influenced by the trend. It told that kids should be free from schools' restrictions. Such a message also fit the concept of Japanese Mary Poppins.

Comet-san is a maid, but she rather likes playing with children. She ignores customs of the human society. Episode 5 shows that aspect very well. Many parents send their kids to a cram school, but those kids hate such education. Comet-san uses magic and secretly takes them out of the cram school. She teaches them how to study joyfully under the sky.

8-3. Yumiko Kokonoe: The Connection Between Idols and Magical Girls

Comet-san starred a singer Yumiko Kokonoe. It is debatable if she should be called an "idol" today. The '60s Japanese idol culture was not like the current one. However, Comet-san was called "idol" in some media. We should not ignore the fact that the series turned her into a national celebrity. It made a synergy between the character and the actor. Later, when the idol culture became more popular, connections between magical girls and idols were intentionally utilized. In that sense, Comet-san is a pioneer of the magical idols.

8-4. Comet-san's Baton and Costume: Modern Witch

Comet-san usually wears ordinary clothes in the series, but she also wears a costume like baton twirlers in the OP. I guess that's the reason why her magical item is called "baton" instead of stick or wand.

Japan imported the marching band culture under the influence of the US occupation and their media propaganda. The first iconic event of Japanese baton twirling was the Tokyo Olympics 1964. Many people saw marching bands and baton twirling in Tokyo Olympics. *26 After that, some magazines said that baton twirling was trending in Japan. Comet-san was made in such an era.

Comet-san's costume made a very modern image of magical girls' appearance. Many magical girls wear flashy mini skirts instead of a dark robe. Comet-san showed that image in the '60s. Maybe we can call her the pioneer of magical girl costumes.

9. How Toei Animation Developed the Genre

After the success of Sally and Akko-chan, NET and Toei Animation continued anime for girls in the same programming slot. However, they did not necessarily stick to the format of Sally and Akko-chan. I describe how Toei Animation developed the genre.

(The explanations down below hugely depend on Tarkus/ Kazumitsu Takahashi's research.)

9-1. Maho no Mako-chan: Mature Magical Girl and Conflicts (1970)

After the end of Akko-chan, Toei Animation started Maho no Mako-chan in the same programing slot.

It is a magical girl story based on the Little Mermaid. Mako, a princess of the sea kingdom, falls in love with a human. She becomes a human and goes to the human world to see the beloved man again. She confronts the human society's problems through school life and interactions with other people. She sometimes solves those problems by using her magical pendant.

Unlike Sally or Akko-chan, it is Toei Animation's original project without any manga source material. That happened because they did not find a good source material at that time. To stabilize the studio's income, they needed to continue the programming slot anyway. Producers and Yugo Serikawa developed the original project in brainstorming. *27

Mako's basic ability and style come from Sally and Akko-chan. When her pendant is exposed to sunlight, she can use various magic. She does not have a particular transformation ability or costume. It's a mixture of Sally's magic and Akko's magical item. It showed the continuity of the franchise/ programming slot. However, Mako also had some changes.

First, Toei Animation changed the target audience. Mako is 15 years old. She is more mature than Sally and Akko. Shinya Takahashi's character design for Mako feels even sexy. Animators drew some sexy shots too. That change was under the influence of the '60s-70s trend.

From the middle '60s to early '70s, Toho's highschool TV show/ film franchise Seishun Gakuen Series was pretty popular. The creators of Mako-chan intended a female version of such school fictions. *28 That is why some parts of Mako-chan are more mature than Sally and Akko-chan.

Plus, shojo manga creators such as Yoshiko Nishitani were already depicting mature themes including sex in the '60s teenager magazines. Manga and anime were gradually reaching young adult audience just like '50s Japanese films did.

We should also remember that shojo rom-com came to include sexy elements in those days. Some of them were seemingly under the influence of Go Nagai's Harenchi Gakuen.

Second, Mako-chan has social commentaries. Sally had some journalistic episodes too, but Mako-chan pushed it forward. Some episodes cover challenging themes such as racism on black people or environmental pollution. Environmental pollution was one of the biggest '70s problems in Japan.

Due to such changes, some episodes have sad, anticlimatic endings. Some guest characters die without any salvation. That storytelling style also decreased the importance of magic. Mako's magic sometimes does not solve any problem of the human society. Mako just promises that she will make a better society in the future.

As a result, Mako-chan became a pretty mature series. Especially the conflict between human beings and the nature became severe. "Do human beings deserve any kindness?" Mako confronts such criticisms from other supernatural entities. She overcomes them by believing in humanity. At the end of the series, Mako abandones magical power and completely becomes a human.

It is debatable if such a sexy and serious style suited the programming slot or not. However, it was an important attempt for the future of the genre. Especially the conflict with human beings became a repetitive theme of magical girls.

9-2. Sarutobi Ecchan: Is It a Magical Girl Anime or Toei's Kids Anime? (1971)

In the fourth series of the franchise, Toei Animation's producer was replaced. A new producer started Sarutobi Ecchan in the same programming slot. The producer switch probably influenced the style of the franchise.

Sarutobi Ecchan is a comedy series about a mysterious girl Ecchan/ Etsuko Sarutobi. She uses supernatual power, and people around her get panicked. She does not have a particular transformation ability or costume. She does not have a spell either. And thus, it is debatable if we call the series "magical girl." In fact, the official website of Toei Majokko does not include it. *29

Ecchan is based on Shotaro Ishinomori's manga series. Toei Animation had connections with Ishinomori from old days, so Ecchan was a convenient material for them. The original manga is Ishinomori's playground. He pursued various ideas such as slap stick, sci-fi, mystery, fantasy, etc. He also did many technical experiments. In other words, Ecchan is a very auteurist manga, not a simple comedy.

On the other hand, Toei Animation's anime adaptation followed the usual style of their kids anime. The anime concentrates on Ecchan, her classmates, and some side characters. It is not so different from Akko-chan in that sense. *30 That was a good thing for the continuity of the franchise, but we cannot say Toei fully utilized the original manga. The protagonist Ecchan has a very unique personality compared to other Toei Majokko heroines, but the series was not as successful as the first two series.

9-3. Maho-tsukai Chappy: The Rise of Franchise Business (1972)

In Maho-tsukai Chappy, Toei Animation got back to the magical girl genre.

Chappy is a little girl from a noble wizard family. However, she admires human beings and the human world. One day she steals her grandfather's magical baton and goes to the human world with her little brother Jun. After some troubles, their parents and a magical panda pet Don-chan follow them. Chappy solves various problems in the human world.

Toei Animation intended "back-to-basics" in this series. Their proposal document says that they go back to Sally's style. *31 Chappy inherited many basic elements from the older magical girls, such as magical item (baton,) iconic spell, animal mascot, protagonist's brother, magical family, interactions with neighbor kids, etc.

The storytelling is basic too. Most episodes depict how Chappy solves problems around her. Since she is a little girl, she does not experience romance, unlike Mako-chan. However, some late episodes include criticisms on environmental pollution and excessive capitalism. Those episodes show Toei creators' enthusiasm for social messages. Yugo Serikawa's direction shined as well.

Unfortunately, Toei Animation's labor conflict got tense during the production of Chappy. In Toei Doga Shiron, Tomoya Kimura explained the history of the labor conflicts and Toei Animation's reactions:

From the late '60s to early '70s, Toei Animation came to depend on contractors and subcontracting studios. Yet, the cost of anime production kept rising, and their deficit just expanded. When Shigeru Okada became the president of main Toei, Toei Animation had to cancel unprofitable business and execute downsizing of the company. In July 1972, they declared dismissal of almost half employees. The labor conflict got tense as a natural consequence. The ongoing anime projects, Chappy included, still continued because they had already shifted to subcontractors in those days. The stories and quality of Chappy's later part were under the influence of the downsizing and following lockout.

However, a new business model was being developed in those days. That is merchandise business. Toei Animation had rights for merchandises of the whole Toei IPs in an early phase. The merchandising profit compensated for the loss of anime production. Since there was the Kamen Rider fad, merch gave big money to them. Since then, Toei Animation had gradually shifted to a merch-driven business model.

According to Kimura, Mazinger Z is the iconic example of merch business. Toei Animation and their partners developed the project so that they made the perfect synchronization of the anime story, toy products, and media exposure. In other words, they developed a franchise business through Mazinger Z.

Magical girls gradually adopted such a style. Toei Animation made Chappy and confronted labor problems at the beginning of of it.

9-4. Miracle Shojo Limit-chan: Insufficient Experiment (1973)

After the end of Chappy, Toei Animation made an anime version of Babel II in the same programming slot. I suppose they had no plan for the next magical girl yet, so they depended on the anime adaptation of the popular manga. After making additional 13 episodes of Babel II, they finally developed Miracle Shojo Limit-chan, a new anime for girls. However, Limit-chan was not necessarily a magical girl.

Limit is a daughter of a scientist. One day she almost dies in an airplane accident. Her father saves her life by making her into a cyborg. Since then, she has lived as an ordinary elementary school girl. Only her father knows about her cyborg body. She has various high-tech items made by her father, such as Magic Bellet or Magic Ring. When she turns the dial of her Change Pendant, she gains super physical power.

The project of Limit-chan was developed by a third-party company called Hiromi Pro. Hiromi Pro is a creative studio made by former members of Mushi Production. In the early phase of Limit-chan, Hiromi Pro prepared a very serious plot. Limit was supposed to have only one-year life span. The proposal also said that Limit's superpower decreases her life. The more she uses the power, the closer she gets to death. However, the TV network requested them to change the plot. The serious part was omitted, and the series became more like other magical girl anime. *32

It does not mean that Limit-chan became an uninteresting series. Masayuki Akehi's direction and Kazuo Komatsubara's sakkan in episode 12 are great. However, they could not pursue the most interesting part of the original plot. Plus, they could not fully utilize the idea of cyborg. Such ideas were fulfilled by another Toei anime in the same year.

9-5. Cutie Honey: The Game Changer (1973)

9-5-1. How Cutie Honey Was Made

It is debatable if Cutie Honey counts as a "magical girl" or not. She is an android, and the series format is pretty different from other early magical girls. Toei Animation's official website does not include it. However, I need to mention Cutie Honey in this section for some reasons.

Cutie Honey is a stoy of Honey Kisaragi, a highschool girl in all-female school. She has a secret identity. She is actually an android made by her father. With the power of her Airborne Element Fixing Device, she transforms into various forms. The main "warrior of love" form is called Cutie Honey. A crime organization Panther Claw kills her father and tries to steal the device. Honey transforms and fights against Panther Claw's monsters.

The project of Cutie Honey was initially made for the magical girl programming slot. In other words, it was a show for girls. That is why Honey transforms into various professional ladies such as cabin attendant or singer. Those forms are based on a survey about girls' dream job from Ribon magazine. *33 They had a pretty different plan for the story in that phase.

The project was developed by Go Nagai and Dynamic Pro. However, Hiromi Pro's Limit-chan won a competition for the programming slot. Cutie Honey lost to Limit-chan. The TV network decided to bring Cutie Honey to another programming slot for boys. The former magical girl turned into henshin heroine for boys. They changed some parts of the plan at that time.

In the preproduction process with Go Nagai, Toei Animation suggested him two inspiration sources:

The first one is Nihon Denpa Eiga's jidaigeki series called Kotohime Shichihenge. *34

Kotohime is a daughter of a shogun and great sword master. She does not want to get married yet, so she disguises herself and goes out of the castle. On the way of trip, she fights various villains and saves common folks.

Heroines with secret identities and female fighters were not uncommon ideas in jidaigeki. In manga, Mitsuteru Yokoyama made such a character in the middle '50s.

Cutie Honey's battle choreography and speech manner feel similar to the style of jidaigeki. It is a very modern series in many points, but the battles give classic impression.

The second inspiration source is a detective mystery series called Bannai Tarao.

Bannai Tarao is a private detective with a secret identity. He disguises himself in various forms and fights villains. In climax, villains ask, "Who are you?" Bannai answers, "I am a man with seven faces. Sometimes I am a private detective Bannai Tarao, other times an artist, a one-eyed driver..." At the end, he says that his true identity is a gentleman thief Taizo Fujimura.

Cutie Honey inherited the tropes from those fictions. In other words, it is a mixture of sword woman jidaigeki and detective mystery.

The project was also under the influence of Kamen Rider and the henshin boom even though the staff themselves do not mention it. Panther Claw is Shocker, and Cutie Honey is Kamen Rider. Back then, so many projects could not be free from the influence of henshin boom. Cutie Honey was one of them.

9-5-2. Cutie Honey's Henshin and Eroticism: Go Nagai's Influences

Go Nagai added two elements to Toei Animation's basic ideas:

The first idea is android. Nagai wanted to make an android girl's story for a long time, so he tried it in Cutie Honey. *35 Since there was already a famous android detective called 8 Man, it was not a surprising idea.

The second idea is eroticism. Nagai made the idea of Honey becoming naked in the transformation process. In those day, Nagai was pretty famous (infamous) for the erotic expression in Harenchi Gakuen series. He criticized the modern morality by disclosing erotic expression in kids' media. He got criticized by many people, but he was also praised. He was a trickster figure of manga. And he brought the erotic element into Cutie Honey.

In so many magical girl fictions, main characters become naked or half-naked in the transformation process. Nagai and Cutie Honey preceded in that trope. Later, Tatsunoko Production followed the sexy style in Time Bokan series.

Honey's transformation gimmick also preceded in another trope: fixed costumes. As we saw above, older magical girls did not have particular transformation costumes. In henshin superhero fictions like Kamen Rider, fixed costume is the norm. Since Honey inherited elements from both magical girls and superheroes, it made the trope of "magical girl becoming naked and wearing fixed costume." Cutie Honey is not the earliest example of henshin superheroine, but it is one of pioneers.

I also need to touch upon the BDSM taste in Cutie Honey. Go Nagai had depicted BDSM since Harenchi Gakuen. The anime had it too even though they did not depict it as hard as Nagai did. *36

Plus, Honey is sometimes severely injured. It is difficult to imagine that Nagai was not aware of its impact.

Before Go Nagai, many artists, such as Taiga Utagawa, already made BDSM cartoon. However, they were released in pornographic media. Nagai brought them into kids' media. That was a pretty shocking and influential event to many people. Later some creators released art/ fictions of tortured or defeated superheroines. In Japanese, it is called "hiropin" (heroine in a pinch) today. I cannot say Go Nagai is the originator of the defeated heroine porn, but he is definitely one of influential pioneers.

9-5-3. Cutie Honey's Abstract World and Bishojo

Toei Animation's staff added some other elements to Cutie Honey.

First, a background artist Eiji Ito made a very colorful, abstract art style. Such a style was made because Producer Toshio Katsuta requested aggressive art style. Ito's hobby was optical art, so he utilized that style in the anime. *37

Sally the Witch had some Western feelings too, but Toei Majokko series was basically set in Japanese suburbs or downtown. They gave pretty vernacular impression. Cutie Honey's psychedelic art style brought modern/ Westernized atmosphere to it.

Second, Shingo Araki started character design in the series. His character style is pretty faithful to Go Nagai's original design, but he also made it cleaner and even more attractive. Especially the eyelashes are distinctive. Araki's commitment to cute girl art was under the influence of Shinya Takahashi's art for Maho no Mako-chan. *38

In an interview, Araki mentioned Nagai's art style and said this:

I thought even nude scenes wouldn't feel obscene as long as they were drawn clean. I drew women's body silhouettes in an unrealistic way, without nuanced lines.

In the first place, Nagai-san's art is not obscene. I thought I should draw such lines.

Sexy art with clean drawing strokes and simple silhouettes. That is what '80s lolicon/ bishojo art style obtained later. In that sense, Araki unintentionally showed a vision of the future. When the anime fandom became a thing and young adult anime fans appeared, Araki was praised as a pioneer of bishojo art style.

9-6. Majokko Megu-chan: The Toei Majokko Masterpiece (1974)

9-6-1. How Megu-chan Was Made

After the end of Limit-chan, Toei Animation started Majokko Megu-chan.

It is a story of Megu, a girl from a magical world. She is a candidate for the queen of the magical world. She goes to the human world for magic training and queen competition. In the human world, she lives with a senior witch's family. She also meets Non, a rival of the queen competition. An examiner Chosan comes to the human world, but he always sides with Non. While helping other people with magic, Megu sometimes fights Non and Chosan.

The project was developed by Hiromi Pro again. It has basic magical girl elements such as magical items, magical spell, and family. The concept is basically faithful to Sally the Witch's formula. However, Toei Animation learned from Cutie Honey's success and brought some Cutie Honey elements into Hiromi Pro's basic ideas. Their concept was "More low-key, cleaner, cuter, and more stylish than Honey." *39 Yugo Serikawa directed the series, and Shingo Araki designed the characters again.

9-6-2. Advanced Version of Cutie Honey and Eroticism

Megu-chan's style became like an advanced version of Cutie Honey for girls.

For example, the protagonist and her rival got some variations of their outfit. Anime characters tend to wear the same clothes everyday. That is partly because they needed to reuse the same cels. However, Megu and Non show different fashion in some episodes. After Cutie Honey showed variations of the battle costumes, Megu and Non did the same thing with ordinary clothes.

Plus, Toei Animation prepared Westernized background art. The story is set in Japan, but the environment is like an European city with terracotta roof tiles and stone pavement. That background art style gave very stateless (mukokuseki) tone to the series. As I wrote in Cutie Honey's section, old Toei Majokko franchise had Japanese environments and vernacular feelings. Megu-chan showed more dreamy images just like Cutie Honey's colorful background did.

They also brought Cutie Honey's eroticism into the early part. Megu often shows her underwear, and the Chosan often peeps in her room. In episode 23, Chosan hypnotizes Megu to wear off her clothes in the school. In the later part of the series, they stopped such erotic expressions.

Plus, the lyrics of the OP theme is quite aggressive:

The two swelling curves on my chest are proof I can do anything...

Even if I don’t put on makeup, ou’re already crazy about me...

Those lyrics show a connection to the '70s idol song culture. Back then, Momoe Yamaguchi debuted at the age of 14 and sang sexual songs such as Toshigoro, Aoi Kajitsu, and Kinjirareta Asobi. Those songs were called "blue sex trilogy." Here are the lyrics of Aoi Kajitsu:

If it's what you want,

I'm fine with you doing anything to me

Even if the rumors say

"She's a naughty girl," it's fine...

And interestingly enough, the lyricist of the blue sex trilogy wrote the lyrics of Megu-chan's OP as well. The series gained pop music's context. I describe the '70s idol culture later.

9-6-3. What Rivals and Sports Genre Brought to Magical Girls

The most important element of the series is Non, the protagonist's rival. In the old days, "rival" was not necessarily a common trope in manga. In shojo manga about mother-daughter melodrama, for example, rivalry is not a necessary element. Rivals became popular through sports genre or so-called Spo-kon.

In 1966, Ikki Kajiwara and Noboru Kawasaki started Kyojin no Hoshi in Shonen Magazine. That manga lauched a very popular sports manga genre called Spo-kon. *40 That trend came to shojo magazines as well.

In 1968, Chikako Urano started Attack No.1 in Weekly Margaret. It is an iconic volley ball spokon manga. In that manga, the protagonist has a good partner called Midori Hayakawa, but she was a rival in early chapters. Later, that trope was developed by Ryoko Yamagishi's Arabesque and inherited by Sumika Yamamoto's Aim for the Ace!

Such competitions and rivalry brought dynamic character relationships into shojo manga. Rivals cause conflicts, but they also understand the protagonists' talent better than anyone. They even become the biggest supporters of the protagonists.

Non has such merits of spo-kon rivalry. She appears as a snobby, elitist girl just like other bullies from shojo manga. However, she sometimes helps Megu for fair competitions. She even thinks maybe Megu is more suitable for the queen. Such dynamics of the relationship led to character-driven and exciting storytelling.

It also made a more dynamic relationship between the magical world and the human world. Magu thinks human beings have many merits while Non priotizes the magical world's logic. Such conflicts existed in Mako-chan and Chappy as well, but Megu-chan managed to depict it from a more neutral perspective. When Megu and Non have a conflict over human beings, the queen accepts both attitudes.

The plot of the queen competition also had another side effect: For the first time in the magical girl genre, a woman became the supreme ruler of the magical world. In the older magical girl anime, kings ruled the world. Megu-chan showed a gradual change of the relationship between girls and the world.

9-6-4. Semi-regular Villain and Battles

Unlike other Toei magical girls, Megu-chan has a semi-regular villain called Satan. Such a devilish character appeared in Chappy too, but he was just a guest villain for one episode. In Megu-chan, Satan repeatedly appears and fights Megu. She even has a semi-regular subordinate. Megu-chan is not a battle-centered series, but the emergence of the regular villain brought a battle theme into the magical girl genre.

9-7. Hana no Ko Lunlun: The Conclusion of Toei Magical Girl (1979)

9-7-1. Lunlun's Story

Hana no Ko Lunlun is a magical girl story set in Europe. Lunlun is an ordinary girl raised by her grandparents. One day a speaking cat Cateau and a speaking dog Nouveau visit her. They say Lunlun is a "flower girl," a heir of a flower fairies' bloodline. The prince of the fairies need Flower of Seven Colors to inherit the throne. The magical animals ask Lunlun to find the flower. She gets "Key of Flower" from them and goes on a journey through Europe to find the flower. When she reflects any flower in the mirror of the key, she can wear any costume she wants. On the way of the journey, she helps other people with magical power. She sometimes meets Serge, a handsome and mysterious cameraman. Serge's identity is revealed at the end of the series.

Lunlun is the first anime that gained all the basic elements of the magical girl genre: magical item, spell, transformation, and mascots. In that sense, Lunlun is the conclusion of the whole Toei magical girl franchise.

9-7-2. Candy Candy's Impact

Before Lunlun, Toei Animation aired Candy Candy, an anime series based on a popular shojo manga series. It is not a magical girl anime. It is a story set in North America and Europe during WW1. The protagonist is an orphan girl Candice White. One day she meets a mysterious boy in a Scottish kilt and calls him Prince on the Hill. When she grows up, she is adopted by a rich man. However, the family members hate her and kick her out. Through a long journey in America and Europe, she gradually finds her way as a nurse and reunites with the Prince on the Hill.

Such orphan stories were very common in old shojo manga. It is obviously under the influence of Western literature such as A Little Princess or Daddy Long Legs. It was a conservative idea to some '70s hardcore shojo manga fans.*41 However, the creators of Candy Candy added a more realistic and strong storyline to that old formula. It was not just a stereotypical tragedy. As a result, it made a historical big hit. Candy Candy is loved by many people even today.

Toei Animation carefully adapted it into anime. They arranged the schedule so that anime would not spoil much about the original manga. They managed to develop the manga and the anime simultaneously. There were some conflicts between the authors and the anime creators, but both of them received positive reactions from the audience.

Lunlun inherited the style and some staff members of Candy Candy. It is a story of a jouney through Europe because of that. Plus, a mysterious prince-like hero appears in the story, just like the Prince on the Hill.

Plus, a toy make Popy got involved in both Candy Candy and Lunlun. Popy is Bandai's subsidary company. They were known for Kamen Rider and Mazinger Z merch, but they did not have popular girls toys yet. In Candy Candy, they finally succeeded in girls' toys. Lunlun inherited Popy's merch business for girls.

9-7-3. The Complete Form of Magical Girl Merchandise

As I wrote in Chappy's section, Toei Animation had developed the franchise business model since the early '70s. Lunlun utilized it. In episode 24, the Key of Flower is broken in a battle with an antagonist. Then, a mysterious entity talks to Lunlun and gives her another key. The new key is more powerful than the original one. It does not only change her costume but also reinforces her ability.

As the episode aired on TV, Popy released a toy of the new key. Or I should say the new key episode was made to introduce the toy. As I mentioned above, Toei Animation experienced the merits of toy-driven franchise business in Mazinger Z. Popy got involved in that process. In Reideen The Brave (1975,) Popy even got involved in the design of the main mecha. *42 Lunlun's new key is one of those cases. In other words, Lunlun took over the method of boys' toys. That attempt had two effects on the genre:

1st, Toy-driven storytelling was brought into girls' anime. Toy makers request anime studios to depict their toys. Anime are commercials for toy makers in that sense. Post-'80s magical girl anime for girls have such aspects.

2nd, it made the trope of magical girls' new items/ power development. In many magical girl anime, main characters gain new items and new forms in the middle of the series. Lunlun developed such a storytelling/ merchandise method.

Lunlun prepared the basic format of magical girl anime as toy commercials. It is a very important point when we consider the business continuity of the post-'70s magical girl anime.

9-7-4. Fairy Fad and Fantasy

The concepts of Western fairies and fairy lands had been well-known through some literature or poem in Japan, so we cannot specify the starting point of Japanese fairy tales. However, it is safe to say fairies' popularity was rising in the '70s.

In 1976, Morinaga & Company put illustrated cards of Cicely Mary Barker's flower fairies into their Hi-CROWN chocolate. *43 It typically shows the middle '70s fairy fad. Back then, fairy tales and Western fantasy were getting popular in some parts of pop culture. I describe it later.

9-8. Maho Shojo Lalabel: Back to Basic Again (1980)

After the end of Lunlun, Toei Animation released Maho Shojo Lalabel in the same programming slot.

It is a story of Lalabel, a girl from a magical world. One day a thief Biscus steals magical items and runs into human world. When Lalabel tries to catch him, she is accidentally dragged into the human world. She cannot return to the magical world, but an old, kind-hearted couple adopts her. She gradually learns life lessons through communications with other people and becomes a human.

In Lalabel, Toei Animation intended a basic magical girl anime. Their proposal document says,

1. Make a family-friendly and happy entertainment

2. Emphasize universal themes (, such as human kindness,) and take distance from trends

3. Express modern feelings of ordinary people, which can be linked to the current kids' mindset and problems

4. Set the story in a familiar town

5. Make high-quality animation so that even grown-ups can enjoy it

6. Make attractive and cute characters

7. Put fortune telling and proverbs into the show, just like Lunlun had flower language *44

Those concepts explain almost everything about the show. Compared to some progressive magical girls such as Megu-chan, Lalabel leant toward a more conservative and family-friendly style.

They also tried to put modern messages into the series. In episode 8, a new teacher comes to the town and tells kids to break old gender roles. Whether you are a boy or a girl, you can do whatever you want. In episode 12, the protagonist tells the importance of free choice marriage. The anime's style was pretty conservative and educational, but their messages were gradually growing out of traditional mindset.

They did not forget to bring new tropes from other magical girls. They had magical item/ merch collab with toy makers. They also made a regular antagonist just like Megu-chan and Lunlun did. Overall, Lalabel is a very basic but up-to-date magical girl series.

9-9. Majokko Tickle: Toei But Non-Toei Magical Girl (1978)

Majokko Tickle is a story of a girl duo. When an ordinary girl Chiko is reading a picture book, she sees another girl running away from a monster in the book. The girl in the book asks Chiko to cast a magical spell. When Chiko casts the spell, the girl comes out to the real world. The girl's name is Tickle. She was confined in the picture book due to her michief. Tickle uses hypnosis magic on Chiko's family and starts to live as Chiko's sister. She causes many troubles in school and neighborhood.

Unlike other '70s magical girl anime, Tickle was made by main Toei's production team, not by Toei Animation. Because of that origin, Tickle is usually not regarded as Toei Majokko. However, the series format is pretty similar to Toei Majokko. Tickle plays pranks with her msagic, and other characters get panicked. Plus, some Toei Majokko creators, such as Hirohisa Soda, Masaki Tsuji, and Keiichiro Kimura, joined the project.

The unique part of the series is that the main characters are a duo. It is said that the concept of girls' duo was inspired by a popular idol group Pink Lady. Pink Lady themselves appear in an episode.

Duos of supernatural characters and ordinary human can be commonly seen in kids manga and anime. Fujko Fujio's Ninja Hattori-kun was already a famous series in those days. In that sense, Majokko Tickle was a very basic kids anime. They have some romance too, but it does not get serious. When Toei Animation's magical girls were leaning toward faminine styles like Megu-chan or Lunlun, Tickle showed a more basic form of magical girls again.

9-10. Why Toei Majokko Is Important

I have spent too many words explaining Toei Animation's magical girl history. Why is that necessary?

First, there were not many magical girls from the '60s to '70s. And thus, when we explain that era, we have to focus on Toei Animation's franchise anyway.

Second, the fact that Toei Animation constantly made magical girls is so important. As I mentioned in Mako-chan's section, they needed to keep developing TV shows to maintain the company. They needed regular income from merchandising. The magical girls gained the continuity thanks to that situation. In other words, the commercial necessity supported the genre. The same goes for the post-'70s magical girls. From the '60s to '70s, Toei Animation showed the typical case of the magical girl business.

However, it also means that they do not need the franchise when they have better options. In 1981, after the end of Lalabel, they stopped making magical girl shows for a while. Producer Yasuo Yamaguchi said, "Girls are stronger than they used to, so they don't have admiration for magic anymore." *45 That is not necessarily true, but Toei Animation did not have a strong motivation for magical girls in that era. They focused on adaptations of popular manga such as Dr.SLUMP or Asari-chan. Other animation studios took over the idea of original magical shows for girls in the early '80s.

Third, Toei Animation prepared most of the basic magical girl tropes in the franchise: magical spell, transformation, magical items, and mascots. They were mixed together in Hana no Ko Lunlun. Each idea is not necessarily Toei's original, but we cannot deny that Toei's franchise brought them into the mainstream media. "Magical girl" basically means variations and successors of Toei Majokko.

10. Other Magical Girls

From the '60s to '70s, there were some epigones of early magical girls. I quickly describe them in this part.

10-1. Followers in Manga

Sally the Witch's success made some followers in shojo magazines. Even Mitsteru Yokoyama himself made a fantasy manga Yosei Nana-chan in 1969.

In 1966, when Sanny the Witch was released, Akira Mochizuki started Mako ni Omakase. It is probably the earliest follower of Sally the Witch.

In 1968, Kiyoshi Takenaka started Majokko Lily.

There was also a more childish type of magical girl fiction. In 1972, Hideharu Akaza started Majokko Luluku. Its childish fairytale style is pretty different from other magical girl fictions. Such kids-friendly magical girl manga have been sometimes made in shojo magazines.

In 1970, NET aired a live-action TV show called Majo wa Hot na Otoshigoro. It is a sexy sit-com inspired by Bewitched and Jeannie. The show is unavailable today, so I cannot cover it in this article. We can get only the theme song and Keiko Takemiya's manga adaptation.

Each of them has their interesting parts, but magical girl manga did not make a big genre from the '60s to '70s. There were many other popular genres such as school romance, so I suppose the authors and publishers did not have a strong motivation for magical girl.

10-2. Fushigi na Melmo: Osamu Tezuka's Struggle for Sex and Popularity (1970)

10-2-1. Mama-chan

In 1970, Tezuka started a kids manga called Mama-chan. It was serialized in Shogaku 1-nensei magazine.

It is a story of a little girl Mama-chan. One day she meets a mischievous angel on a road. The angel says that he stole magical candy from the heaven. Blue candy makes any living thing grow ten years older. Red candy makes them grow 10 years younger. The angel lets Mama-chan use the candy. She uses the candy to solve various problems around her.

As you can see, the plot is probably a variation of Princess Knight. In both series, the angels give the protagonists supernatural things (male soul and magical candy) and those supernatural things change the protagonists. It is one of Tezuka's shojo romance formats. It was not the first time that Tezuka expanded the idea of Princess Knight. In Little Yokko's Here! (1962,) he depicted a modern girl getting a male soul from angels.

Mama-chan also shows influences from Disney and Western folk tales, just like Tezuka's older manga did. It has good parts of Tezuka's old shojo romance manga.

10-2-2. How Mama-chan Turned into a Sex Education Anime

Osamu Tezuka had a pretty bad time in the early '70s: Other creators' fictions intimidated him severely in those day. Gekiga, his pupils' manga, tokusatsu TV shows, etc. On the other hand, Tezuka's new manga, such as Burunga the 1st or Dororo, did not have a commercial success. Manga editors started to say, "Tezuka is over."

Even Mushi Pro, Tezuka's own anime studio, avoided Tezuka's IPs. They started to animate other manga creators' manga. Tezuka quit the president of Mushi Pro around that time. He was losing his positions in both manga and anime.

In such a dark era, Tezuka started a new theme in shonen manga. That is "sex education." In 1970, he started Yakeppachi's Maria in Weekly Shonen Champion. He also started Apollo's Song in Weekly Shonen King.

Yakeppachi's Maria is a story of a highschool boy Yakeppachi. His desire for motherly figues becomes ectoplasm. It comes into a sex doll, and the sex doll becomes a human. She is named Maria and dates with Yakeppachi.

Apollo's Song is a story of a boy with mental illness. He escapes from a mental hospital and meets a beautiful lady. Through communication with her, the boy learns sexual relationships and love.

Those manga were obviously reactions to Go Nagai's Harenchi Gakuen. As I mentioned Cutie Honey's part, Harenchi Gakuen made a big hit and caused a huge controversy. Tezuka, Shonen Champion, and Shonen King reacted to it by showing "sex education." They intended to educate children through manga and magazine articles. We cannot say they were successful attempts. Parents criticized sexual expression in Tezuka's manga anyway. Tezuka had to wait a few more years until his resurgence with Black Jack.

A shady businessman from music industry helped Tezuka at that time. The name of that businessman is Yoshinobu Nishizaki. *46 I suppose many people remember him as a producer of Space Battleship Yamato. He became an agent of Tezuka in the early '70s and immediately got an agreement on a TV anime project from TV Asahi. TV Asahi gave green light to an anime adaptation of Apollo's Song. It shows how competent Nishizaki was.

Mushi Pro did not make Tezuka anime anymore, so the anime was developed by Tezuka Production. They made a pilot film, but the TV network did not like the mature style of the series. *47 Tezuka Pro changed the project into an anime adaptation of Mama-chan, and they put the sex education theme into it. In other words, They mixed Mama-chan and Apollo's Song together. It became a sex education anime based on the kids metamorphosis manga. Plus, they changed the title from Mama-chan to Melmo due to a trademark conflict. "Melmo" stems from metamorphosis.

10-2-3. Whether Melmo Is a Magical Girl or Not

It is debatable if Melmo counts as a magical girl. If we assume that magical girl means any heroine with magical elements, Melmo is undoubtedly a magical girl. Fushigi na Melmo is a magical girl series just like Princess Knight can be called so.

As I showed in the prehistory part, Tezuka made various magical ideas in the '50s manga, and those elements are linked to the origin of magical girl genre. Melmo is linked to that old origin of magical girls, but it was not made as one of "genre manga/ anime." The conclusion depends on your definition of magical girl. If you emphasize the continuity from Toei Majokko, Melmo is not a magical girl. If you focus on "magic," Melmo is a magical girl.

10-3. Suki Suki Majo-sensei: The Earliest Henshin Heroine (1971)

Suki Suki Majo-sensei is a live-action TV show made by Toei Ikuta Studio. Ikuta Studio is known for Kamen Rider series. Suki Suki Majo-sensei is one of their earliest projects.

It is a story of Hikaru Tsuki, a space peacekeeper from Planet Alpha. She disguises herself as a school teacher and communicates with children. She has a magical ring called Moonlight Ring. The ring consumes moonlight energy and turns it into magical power. When she says, "Moonlight Power," she can use various supernatual power. With the power of the ring, she helps various people and fights villains.

The concept of the series was apparently under the influence of Bewitched or Comet-san. However, the source material is Shotaro Ishinomori's shojo manga Sen-no-me Sensei. The original Sen-no-me Sensei is a serious psychic battle manga based on Mutant Sabu. The story of the manga is set in a highschool. It is pretty different from the TV adaptation.

The early part of the TV show is a happy comedy set in an elementary school. Most episodes depict little kids and their troubles. The protagonist's magical power is not seriously depicted. The tone of the show is similar to Comet-san or Sally.

However, the creators added tokusatsu superhero elements to the later part of the series because of Kamen Rider's commercial success. The tone of the series drastically changed after that.

In episode 12, a supervillain Zolda appears. Hikaru defeats them with her magical power.

In episode 14, a messanger from outer space visits Hikaru and gives her a new power. When she uses a new transformation compact, she transforms into a superheroine Andro Kamen. In episode 18, a regular villain Kumondeath appears. The series's main focus shifts to battles between Andro Kamen and Kumondeath.

Before Andro Kamen, the idea of henshin superheroine was not a thing on TV. Andro Kamen is even earlier than Cutie Honey, Orange Fighter, or Tackle from Kamen Rider Stronger. I think it is safe to say she is a pioneer of TV superheroine.

The Kamen Rider staff directed action scene pretty well, but it is debatable if the style of the later part fit the show or not. It feels like they mixed apples and oranges. It also feels like the superheroine element prevented them from developing side characters. Majo-sensei was a too early attempt. The superheroine tokusatsu concept was fully pursued much later, in the '90s Toei Fushigi Comedy.

10-4. 5-nen 3-kumi Maho-gumi: Kids' Team and Magic with Demerits (1976)

5-nen 3-kumi Maho-gumi is a magical tokusatsu TV show made by Toei Tokyo Studio. It was aired after the end of The Kagestar.

It is a story of ordinary elementary school kids. One day the kids meet the witch Barbara. Barbara gives them "MJ Bag" and various magical items because they helped her. Barbara says they can use the items as they want. The items can make them happy but also bring misfortune. The kids keep it a secret for themselves and solve various problems with the magical items.

Maho-gumi inherited two basic ideas from the magical girl genre: magical items and spells.

Needless to say, the magical items have toyetic gimmicks. When kids use magical items, they need to cast a spell "Abcra-tararin Cracra-makashin."

Interestingly enough, one of the magical items has a demerit. An item called Mangan Key is an almighty device. It can grant any wish. However, it always brings misfortune called "payback." The bigger the wish is, the more serious payback becomes.

Another unique part of the show is that the protagonists make a team. It does not focus on a single protagonist. Each member has unique pesonality, such as foodie, intelligent, coward, tomboy, or kind. The chemistry of the kids' team provided dynamics of the story. It feels similar to Shonen Tanteidan franchise. I suppose Maho-gumi was supposed to be a magical version of such child detective teams.

The witch character is unique too. Machiko Soga played Berbara. Before Maho-gumi, she was famous as the actor of Oba-Q. In Maho-gumi, she showed her live-action skills and became a veteran tokusatsu villain actor. Some may remember her for Rita Repulsa from Power Rangers. Her look and acting style perfectly suited the personality of Berbara. She is depicted as a villain, but she's also a very charming comedy relief. She made the catchy part of the show.

Kids' team, elementary school slice-of-life, toyetic magical items, spells, comedic witch, and risky magic with paybacks.

The mixture of those elements was repeated in Ojamajo Doremi. I am not sure if Maho-gumi had an influence on Doremi or not, but it is a predecessor of Doremi's style.

10-5. Tomei Dori-chan: Basic Magical Girl Live-Action (1978)

Tomei Dori-chan is Toei Ikuta Studio's tokusatsu TV show. It aired in Super Sentai's programming slot after J.A.K.Q. Dengekitai's commercial failure.